The Bone Child Chapter 1: "The Orphan's Skull"

A hale child of man arises, ready to fight

The Bone Child

Chapter 1 - The Orphan’s Skull

Orphan was not an orphan, but the children of Coldhome had called him that for over a year.

His mother, Fair Holca, had died more than a decade ago, back when he was only two, and she hadn’t named him yet. It was sour luck to give a babe a name before his third year out of the womb. The Darkling Things might twist the child or take it, with a name given too early. And today would be Orphan’s thirteenth birthday, and thirteen was an unlucky age to be turning. The alders and the crone-seer both agreed on that.

But Orphan’s name wasn’t Orphan, and luck was what the unlucky relied on, in his short experience. Misfortune is what the helpless sow, and ‘hapless’ is just another word for fools. That was one of his father’s oft repeated lessons.

And unlucky or no, Orphan once possessed another name, and not so long ago. Five years past, he was merely “Boy,” to the community, but the Elder Bruin and Oksi the Raven agreed to call him “Young Hal,” after his father’s name. His father was Hal the Tall, Hallen Crowspear.

Hallen Crowspear had been a great warrior and a raider abroad. Then Hallen Crowspear sought his fame and fortune elsewhere, out West. There were few raiders who came this far out, but there were many fortune seekers who passed through Coldhome on their way to the Giants’ Crater. Orphan’s father, Hal, was the rarest breed of all: the man who stayed here when he came and lived to tell his tales.

In his time, Hallen had defended the village from a handful of raiders far worse than himself, hard and hungry bandits the lot of them. And twice he had helped Oksi the crone-seer to protect their homes from actual gheists that gusted in off the bitter winds of the Icewraith Tundra.

“Oh, Hal the Tall has the heart of a giant,” or so the nodding villagers had often repeated to themselves, before last year. But what they whispered to each other now was that Crowspear was possessed by the lust for gold and bones. He had the eating envy of shimmering silver and treasure, and perhaps even for Darkling objects! That must have been why he went over.

It was better to stay in Coldhome than to venture over the Edge, of course. They all agreed on that point. “Better to stay here warm by the hearth than to seek death and worse in all those ruins!” And for a time, Young Hal had agreed with them. Until last year, of course. Until his father took up arms and armor again and told his son to stay back, stay here, with Ruthvin and Allabeth.

Young Hal had been confused by his father’s sudden decision and departure, but it made sense to him now. A sort of sense, anyway. And now he was about to follow in his father’s footsteps.

Orphan strode purposefully past Yenneg and his two younger sisters, throwing snowballs past each other, hardly hitting their targets but laughing all the same. They played dozens of dull games every day. But now “Orphan” was no longer invited to them.

They considered him cursed now, because of their parents’ disapproval and Coldhome’s many superstitions. After all, the boy’s mother had died when he was too young to be named. And now his father had vanished from the world above when the boy was almost a man grown.

The boy must be the trouble then. Orphan! He walked past the other children as they joked and jeered in his wake. They were crueler than usual today. Yet he would not let their idle words and silly faces keep him from his journey. Not today, when he turned thirteen.

He passed Oksi’s small wooden hut, the tall thatched roof covered in a white blanket like all the other houses. The crone-seer was away watching for spirits from the East, off the Great Tundra. Then he passed the long Aldrahall, where the Elder Bruin and the alders were meeting in council on many matters, none of which mattered at all to Orphan today.

He came at last to his “home,” or rather, his foster’s home. It was the house of Ruthvin Runemaker, the town’s bone-smith. Ruthvin and Allabeth made their living the way Ruthvin’s father, great-father, and great-great-father before him had done. They traded Grimm-Marks and Aquiline scrolls and other coin and treasure in return for arms and armor, iron and leather or bones or both. And Orphan would soon have his own blade and bones, or else walk out unequipped. Today was the day.

Ruthvin was outside at the grindstone. He was sharpening a short axe or hatchet or some other weapon. The smith looked up at him briefly, smiled softly, but the lines around his eyes creased further with new worries. Orphan smiled back and waved to him before heading inside.

Allabeth was cooking a large breakfast over the dwarf-work stove. She hummed with the tune of the sung-stone rocks while they boiled the water in the pan and heated the eggs and pork. Orphan almost waved to her too, but he felt a sudden stab of guilt. He didn’t speak. She seemed so happy there making their next meal, and he didn’t want to ruin that.

The boy left the large kitchen and went to the store-room at the very back of the house. That was where his father's last belongings were kept, along with all the makings of a warrior’s gear. He grabbed all he could carry, then scurried like a squirrel back outside, hoping Allabeth didn't notice.

When Ruthvin looked over his shoulder to see what all the rattling was about, Young Hal showed him the bundle in his arms. Ruthvin nodded sadly. They exchanged no words until Young Hal was fitted with a leather tunic and greaves, and bits of iron dotted his shoulders, chest, and boots.

“How shall we cover your head?” Ruthvin asked, stroking at his long black beard. That was a nervous habit of his.

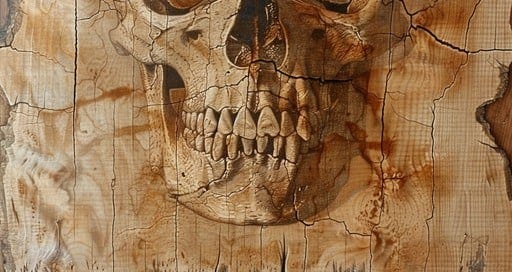

The boy brushed his hay-yellow hair and opened his mouth, but the words wouldn’t come out. Instead he held out the large dwarven skull that his father had found years ago. Ruthvin stopped stroking his beard. Instead he frowned and sighed. Then he nodded, as if to himself, and took the offered skull.

When the bone-smith had finished his work, Young Hal did not feel so young anymore. He saw differently now, through the dwarf-mask’s hollow eyes. His head felt warm and cushioned from the goatskin padding, but his lips still felt cold, even with the jaws and teeth fitted close around his mouth with string, iron, and more leather. The back of the dead dwarf’s skull had been chiseled out and scraped down to dust the rest of his armor. The bone-dust would make it all stronger, once the runes were carved and the magic words spoken.

Ruthvin was seated at his feet, but the tall man’s eyes were still level with the boy’s. “What Name shall I carve on the skull for you?” asked the smith. “What Word will be your Ward?” Ruthvin had a small tear on his face. He didn’t wipe it away.

The boy thought long and hard for what seemed forever, but found no answer forthcoming. He shook his head, heavy with the weight of his new helmet. Many minutes passed, and the two of them waited in silence.

Then the sun glinted in his eyes when the clouds moved overhead, and he took a step back. He finally found some words and answered his foster father, the bone-smith. “A word like ‘Boy’ is too simple,” he said. “But ‘Hal’ is not good or true, nor ‘Young Hal,’ either. If I go to find my father’s bones, I do not want his dead name on my head, or the old names that never protected me.”

“What shall you have then?” Ruthvin the Runemaker continued to stare at him with dead eyes through warm tears.

Allabeth had left the house long ago, in a fury, and she had been weeping too. But the council didn’t know yet, nor the lady shaman. It was his time. He would have his steel dagger and his simple wooden shield. He would have the short Aquiline sword on his back. But what word or name would protect his head, and fill his whole body with cold, true magic?

Then it came to him. The boy smiled and laid his right hand on Ruthvin’s shoulder. He whispered to him close, then laughed in glee at the bone-smith’s consternation. Ruthvin made a worse face, anger and sorrow competing on his features, his brows knitted like crossed thunderbolts. He gritted his teeth.

The boy wiped the tears away from his foster-father’s cheek, then placed his left hand on the bone-smith’s other shoulder and pressed hard. “It is true,” the boy whispered, “and it is time.”

Ruthvin Runemaker snorted, nodded and smiled grimly, but he stood up and went straight to work. No more tears fell from the smith’s face, only sweat, and a single drop of blood fell from his hand from where he struck the skull too strongly and swiftly with the stroke of his hammer and chisel.

And finally, on the temples of the dwarven skull lacquered over a frosty blue, there was carved a single solemn word in

Rûnic:

ÔłÛł’X

And Orphan smiled. For it was his name now.

“ORPHAN.”